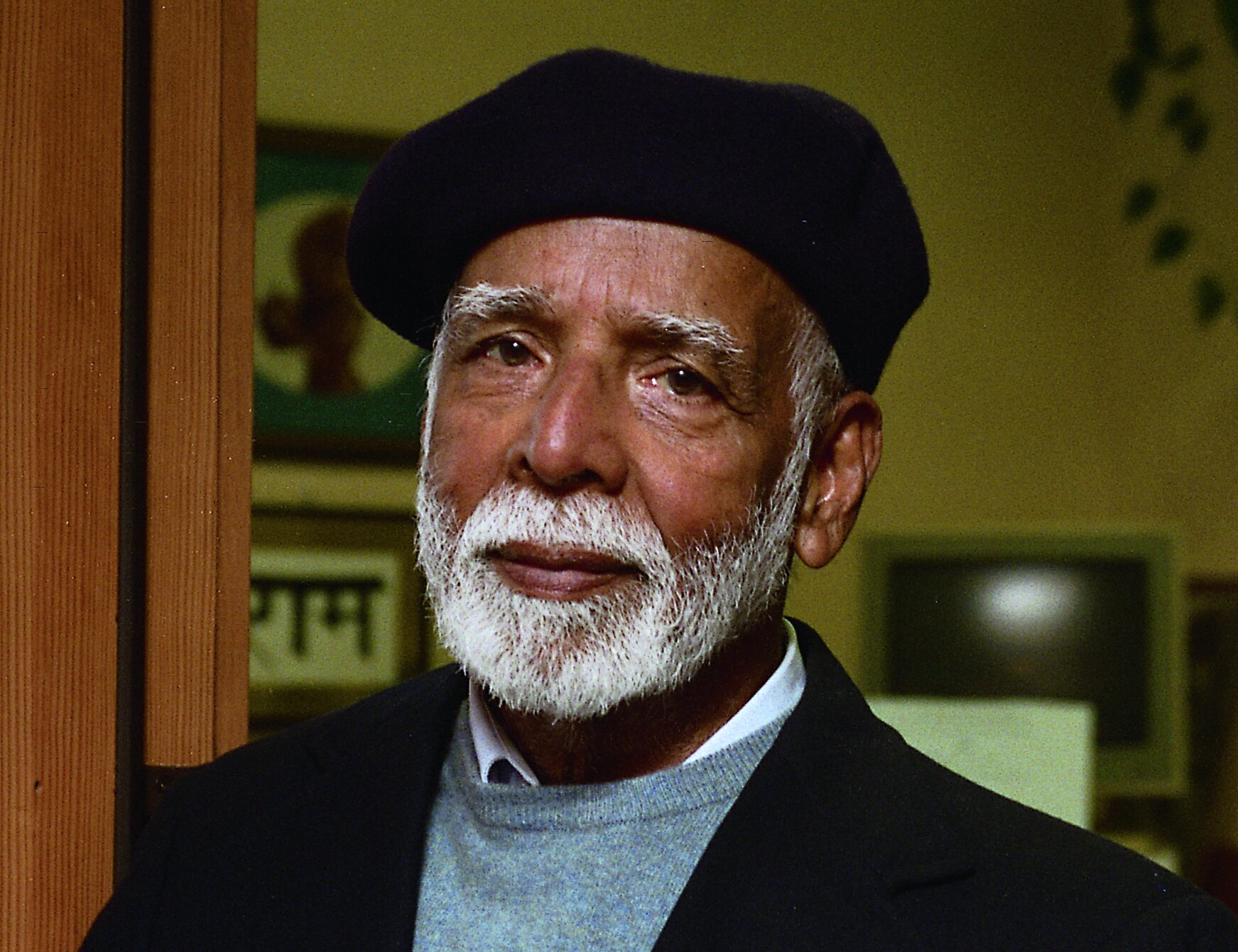

“Most of us have grasshopper minds,” Easwaran writes in this week’s reading, “dispersing our attention, energy, and desires in all sorts of directions and depriving us of the power to draw upon our deeper, richer resources for creative living.”

Meditation is the solution to this dispersion: “Meditation is integration.” This integration is the key to using all our intelligence and creative faculties, the key to peace and happiness.

In this week’s essay, “The Path of Meditation,” Easwaran presents his eight-point program for realizing our potential. Let’s start by reading the first half, pages 127–131 in Climbing the Blue Mountain, in which he covers the first point, Meditation on a Passage.

“For what purpose am I here? Where am I going? What awaits me after death?” The Hound of Heaven is on the trail of every one of us, Easwaran writes, and these questions will not leave us alone. “Without answers to these questions, life has very little meaning.”

This week as we read pages 121–125 of Climbing the Blue Mountain, Easwaran leads us to take evolution into our hands by “[turning] inwards to discover the source of meaning and fulfillment right within yourself.” This discovery in turn embraces the whole of life and brings us home into the arms of the Lord.

Whether you like it or not, whether you know it or not, secretly nature seeks and hunts and tries to ferret out the track in which God may be found. – Meister Eckhart

With this epigraph Easwaran begins his essay “The Hound of Heaven,” in Climbing the Blue Mountain. The Hound cannot be evaded, and its chase may manifest as insistent questions about the meaning of life.

“It is a sure measure of the Lord’s love,” Easwaran tells us, “that whether or not we want to think about it, he will find ways to go on asking until finally we do hear. Many of the tragedies and reversals of life are special delivery letters sent straight from the Lord to our door, reminding us that other activities will bring us very little satisfaction until we discover why we are here.”

This week, let’s read the first half of this essay, from page 117 to the top of 121, ending with “…fulfillment right within yourself?”

Last week Easwaran shared how Granny used a stolen mango in his village school days to teach him about sakshi, one of the Thousand Names of Sri Krishna meaning “the internal witness.”

This week as we read pages 111–116 to finish his essay with that same title in Climbing the Blue Mountain, he narrates how Granny renewed the lesson when he was in high school by questioning him about rumors of his impoliteness to a neighbor’s sister. “What does it matter what his sister says?” Easwaran replies.

“‘What about yourself?’ she would ask. ‘Don’t you want the respect of yourself?’

‘Of course, Granny.’

‘Well, then,’ she would say, ‘you have to earn it.’”

The security that comes from gaining the respect of our own Self, Easwaran says, “cannot be shaken by anything on earth.”

"…Someone inside is watching everything, someone who never misses a thing,” Granny tells Easwaran in the story he uses to start this week’s essay, titled “The Internal Witness.”

This internal witness is our real Self, hidden by many layers of conditioning. “Our whole job in life is to remove these veils – that is, to overcome all the compulsive aspects of our surface personality.”

This week let’s read the first half of this essay, pages 105–111 in Climbing the Blue Mountain, ending with “…we are beginning to identify with our real Self.”

Easwaran describes an entry into the unconscious in this week’s reading, pages 98–104 of Climbing the Blue Mountain.* Last week he lead us past the exterior in this “house of the mind.” Now we explore the deepest and highest reaches.

Of course this represents the spiritual journey, on which he is indeed leading each of us. As we progress, “We know what we have to do. It will be terribly hard, but we need to get control of the very source of power in ourselves – get into the basement and wire all those dynamos together to harness the full power of our desires.”

The labor is monumental, but so are the benefits. We look forward to hearing your insights and reflections.

Like owners of an elegant Victorian home, many of us focus elaborate attention on the exterior: our appearance and surface pursuits. To find our divine core, however, “we cannot stay outside. We need to open the door of the Victorian house of the mind and go in.”

In this week’s essay from Climbing the Blue Mountain, Easwaran uses this “homely illustration” to help us remember an eternal truth: “that by whatever name we call him, the Lord of Love is always present in the depths of our consciousness. Nothing we do can displease him. And human life has one single purpose: to discover this divine Self through the practice of spiritual disciplines, of which the foremost is meditation.”

This week let’s read the first half of “The House of the Mind,” pages 93–98, ending with “…impossible to go at all.”

“We get detached from ourselves, from our own ego, by gaining control over the thoughts with which we respond to life around us,” Easwaran explains as we conclude his essay “The Ticket Inspector” by reading pages 86–91 of Climbing the Blue Mountain.

And while detachment may sound negative, he emphasizes that its positive implications are tremendous:

“I would even go so far as to say, on the basis of what I myself have experienced, that we can reverse any negative tendency in our personality by refusing to let negative thoughts have their way. This is a far-reaching statement, for it means that positive thoughts are already on board the train. All we have to do is make sure their places are not usurped. Love, for example, is our nature.”

We are working together to cultivate detachment and realize our loving nature. We are so glad to be traveling this way with you!

Easwaran describes the mind as a crowded train station in this week’s essay from Climbing the Blue Mountain. Our thoughts are the passengers, often hitching rides and forcing unscheduled stops.

“Goodwill has a ticket. Compassion, forgiveness, love, wisdom, are all qualified travelers with lifetime passes. But ill will, jealousy, impatience, greed, and resentment have no tickets. They should never be allowed on our trains.”

Fortunately, “Meditation functions much like a ticket inspector, polite but very firm.” This week let’s read the first half of this essay, pages 81–86, where Easwaran sets the scene and assures us we too can learn to perform this tremendous feat of traffic control.

The secret of happiness lies in forgetting about ourselves and our problems, Easwaran explains in simple language in this week’s essay, pages 73–80 of Climbing the Blue Mountain. He also illustrates the message with this colorful story:

“When my niece was with us in California some years ago, she had her heart set on being a hopscotch champion. It seemed to me that she was making good progress, but the subtleties of the game escaped me. So finally I asked her, ‘What’s the secret of championship hopscotch?’:

“Her answer was right to the point: ‘Small feet.’

“Even I could appreciate that. If you have constable’s feet, so long and broad that they cut across all the lines, you can’t get anywhere in hopscotch. Life is like that too: if you have a big ego, you can’t go anywhere without fouling on the lines. But there are people who have petite, size five egos, who find it easy to remember the needs of others. They may not have much money or be highly educated, but they are loved wherever they go.”

“As long as we look upon joy as something outside us, we shall never be able to find it. Wherever we go it will still be beyond our reach, because ‘out there’ can never be ‘in here.’” – Eknath Easwaran

This week let’s finish Easwaran’s essay “Chasing Rainbows” in Climbing the Blue Mountain, reading pages 67–71. Drawing on Gandhi and the Bhagavad Gita, he helps us see the temporary nature of desire, and the lasting joy found in freedom from the sense of I, me, and mine.

Easwaran repeatedly raised “a question of priorities” in last week’s reading, noting that “if only we make it our number one priority, as young Thérèse did, no matter what difficulties come in our way, our love cannot help but grow.”

This week, as we finish his essay “The Supreme Ambition” in Climbing the Blue Mountain, he shows how the inspiration of someone in whom we see the Self’s beauty manifested drives us into action on such changes:

“The deep longing to be like the one we love gives us motivation to make great changes in ourselves – many of which are distressing – not only with courage but with a fierce sense of joy.”

He says this transformation even becomes “inevitable, inescapable” when we begin to feel drawn to the Self.

Let’s read pages 62–67 to finish this essay and begin the next. We are eager to hear what you feel drawn to in this reading!

“The only purpose which can satisfy us completely, fulfill all our desires, and then make our life a gift to the whole world, is the gradual realization of this Self, which throws open the gates of love. We cannot dream what depth and breadth of love we are capable of until we make the discovery that this divine spark lives in every creature.”– Eknath Easwaran

Using the example of Thérèse of Lisieux, Easwaran puts before us the majesty of this supreme ambition in this week’s reading, pages 57–62 of Climbing the Blue Mountain.

How can we learn such love? It is helpful to draw inspiration from those like Thérèse who practice love in their daily lives. Yet, Easwaran emphasizes, “we all have the syllabus of love right inside us, printed on every cell. We need look no further afield. There burns in the recesses of our consciousness a divine spark of pure love, universal, unquenchable.”

“What supports life, according to the mystics, is the principle of unity; what destroys life is separateness, the negation of this principle.” Last week Easwaran helped us to see this unity as always within us – but simply forgotten.

This week let’s read pages 50–56 in Climbing the Blue Mountain to finish the essay. Here Easwaran shows that it is by appealing to that deep sense of unity that we can get the best out of others and “turn against the current to find our true nature, which is oneness with all life.”

The principle of unity supports life, and our selfishness and separateness are simply a forgetting of this truth. “Samadhi according to this interpretation,” Easwaran explains in this week’s reading, “is not union with God but reunion.”

In this week’s short reading, pages 47–50 in Climbing the Blue Mountain,* Easwaran illustrates this compassionate perspective with an engaging story from the Hindu tradition, the story of a modern magician, and the Bible’s Prodigal Son.

May we draw on the support of our teacher and this dedicated community to leave behind separateness and recall our unity.

“Spiritual wealth” is the topic of our current essay in Climbing the Blue Mountain. As we complete that chapter this week by reading pages 42–45,* Easwaran describes how we can make our lives a gift to the world.

“For better or worse, personal example is a force,” Easwaran states in this week’s reading. “[I]f we indulge our personal desires, even if only in little things, it encourages those around us to do the same.”

“How and what we eat, what we drink, how we talk to people, how we deal with difficulties – all these things influence others deeply, especially children. In this sense there is a field of forces, selfish and unselfish, swirling around every one of us.”

By learning to be selfless, we can choose the way we influence others. “Then you become not only rich but a real philanthropist, distributing wealth wherever you go.”

“The mystics have a different way of thinking about wealth,” Easwaran explains in this week’s reading, pages 37–41* in Climbing the Blue Mountain. “It is not how much we have that makes us rich, they say; it is how much we give – not only of our resources, but especially of ourselves.”

To bring this truth to life, Easwaran presents us with the example of Gandhi, a “zillionaire.” Easwaran tells the story of his own visit to Gandhi’s ashram, anchored by the evening prayer meeting:

“As I watched, Gandhiji’s eyes closed in concentration. His absorption in the verses was so complete that you could almost see the words filling his small frame. Suddenly I understood the answer to the question I had come with. Here was the source of all his wealth – his power, his love, his wisdom, his tireless service. He had turned his back on his little ‘I,’ his ego; now he lived in all.”

“All of us have a supreme jewel in the depths of our hearts, and we have come into life for no other purpose than to discover this jewel here on earth while we are alive.” With this matter-of-fact revelation, Easwaran entices us to seek the Atman: the Self, the unchanging truth, abiding joy, and flawless beauty who we really are.

And when we do – by practicing meditation and the allied disciplines to the very best of our ability – the results are both predictable and astounding:

“First your health improves; some long-standing physical problems may be alleviated. But don’t stop there. In the next stage you will learn to solve difficult emotional problems. If you persist, you may make your whole life a work of art, so that not only you but those around you benefit from your patience, understanding, love, and wisdom. Gradually even people who do not like you learn to respond to you, by responding to what is deepest in themselves. Then your life is a lasting contribution to all.”

But even this is not enough, Easwaran explains:

“After you have solved physical and emotional problems and made your life a creative force, one great achievement remains: the personal discovery that all of us are one and indivisible.”

Our reading this week is Chapter 2 of Climbing the Blue Mountain (pages 29–36).

In this week’s reading Easwaran describes “a kind of gnawing hunger deep inside” that led him to meditation. For example:

“One problem that began to torment me at the university was that though I knew how to teach my students about Shakespeare and Spenser, I did not know how to teach them what they most needed and wanted to know – how to live.”

Relief came as meditation developed the capacity to help:

“As meditation deepens, wherever you find sorrow – in the lives of your friends, in a community crisis, even in a tragedy on the other side of the globe – that sorrow is your own. But at the same time, this deeper sensitivity releases the capacity to help. You find ways to help others solve physical problems, set emotional difficulties right, repair their relationships, and even forget their personal problems in making a lasting contribution to the rest of life. In this way the power of sorrow is harnessed, and the deep gnawing hunger I spoke of begins to be relieved.”

Let’s finish Easwaran’s essay “Taking the Plunge” by reading pages 22–27 in Climbing the Blue Mountain (starting on page 22 with "Second, meditation brings vibrant health"). We are eager to hear your reflections in the comments below.